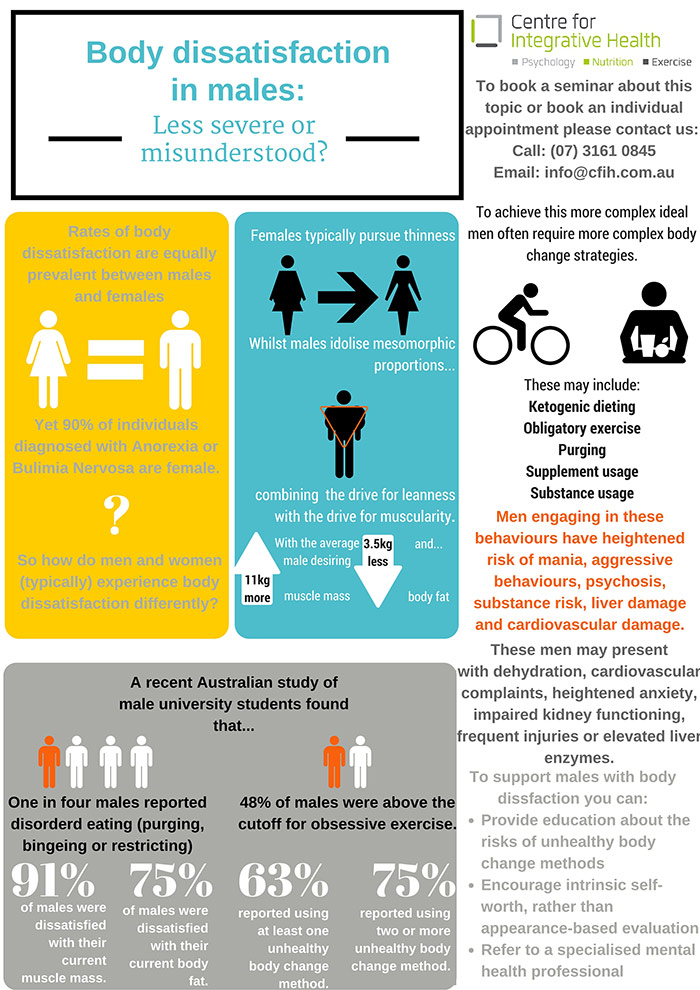

Eating disorders and body dissatisfaction have historically been relegated to the domain of women. After all, 90% of individuals diagnosed with Anorexia Nervosa or Bulimia Nervosa identify as female.

Despite this, research is increasingly showing rates of body dissatisfaction in males is similarly prevalent to rates in females. Males experiencing body dissatisfaction are at an increased risk of being diagnosed with an anxiety or depressive disorder and are more likely to also exhibit low self-esteem.

Despite this, body dissatisfaction in males is not linked to eating pathology such as bingeing, purging or restricting. So either males experience body dissatisfaction without any desire to act on their dissatisfaction or there is something we are misunderstanding about male body change behaviours?

The obvious starting point in exploring this question is to better understand gender differences in body dissatisfaction. Body dissatisfaction in males is typically more complex than in females. Whilst females frequently exhibit a drive for thinness, males more commonly desire mesomorphic or “V-shaped” proportions. This build combines not only the drive for thinness/leaness but also increased drive for muscularity, with the average male desiring 3.5kg less body fat and 11kg more muscle mass. Due to this complexity, it is understandable that males require more complex body change strategies than females.

Although the literature is conflicted with how to define or categorise men’s body change strategies, one term frequently used is Muscle Dysmorphia. A sub-diagnosis of Body Dysmorphic Disorder, individuals have a distorted perception of their muscle mass (muscle belittlement), experience distress related to their muscle appearance and will be engaging in strategies to conceal or change their muscle appearance.

These high-risk body change strategies are more prevalent than both Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa and can be seen in as many as 1 in 10 individuals in the body-building community. High-risk strategies include:

- Weight gain strategies (bingeing, high kilojoule/protein/fat/carbohydrate dieting)

- Weight loss strategies (purging, restricting, laxative use,

- Ketogenic dieting (cycling between high protein and fat/low carb and high carb periods)

- Supplement usage

- Substance usage

- Obligatory exercise (exercise impairing with social/occupational functioning, distress when unable to exercise and tolerance/withdrawal symptoms to exercise)

Although Muscle Dysmorphia is a relatively new concept, with most research into the disorder occurring in the past ten years, we do have some initial understanding of how it develops. Research has shown that over the past 50 years there has been increased sexualisation of the male body depicted in the media, with increasing inclusion of more semi-naked, lean and muscular males in magazines in advertising.

Additionally, similar to research on Barbie dolls, male action toys have become increasingly more muscular to the point that their proportions are as unattainable as their female counterparts. This exposure to mesomorphic ideals through the media has been shown to increase male body dissatisfaction.

Researchers have also found that males who experience late-onset puberty, and consequently more difficulty building muscularity, are more likely to be dissatisfied with their body. Finally, males with muscle dysmorphia are likely to have a similar psychological profile to females diagnosed with Anorexia Nervosa or Bulimia Nervosa including neuroticism, low self-esteem, perfectionism and extrinsic self-worth in appearance/fitness.

So how common are these difficulties in Australian men? A recent study involving males attending a Queensland university found that approximately 63% were engaging in at least one unhealthy body change strategy (including substance use, obsessive exercise, or eating pathology). One in four of the students questioned were engaging in two or more of these strategies. About half of the sample were engaging in obligatory exercise, with high levels of supplement usage and above average usage of substances for appearance/performance enhancing purposes.

Additionally, 25% of males displayed some form of disordered eating (restricting, bingeing and/or purging). More than 90% of the sample was concerned with their muscle mass, whilst over three-quarters of the sample desired less body fat.

Eating disorders, as currently defined, have the highest mortality rate of any mental health condition. So how do male body change strategies compare to this? Unfortunately, outcomes of utiliisng male body change strategies are very similar to those of Anorexia and Bulimia Nervosa. Males with muscle dysmorphia are often engaging in the restricting and purging underpinning Anorexia and Bulimia Nervosa, so are at heightened risk of ???. In addition to this, due to the too-common abuse of substances in this population, males are also at increased risk of experiencing a manic episode, heightened aggression, psychosis, cardiovascular difficulties and liver damage amongst others.

With all of these risks, and considering such it’s increasing prevalence, health professionals are understandably concerned with how to treat this presentation. The first concern with treatment is that males with body dissatisfaction are less likely to present than females, and males with muscle dysmorphia are less likely again than those with Anorexia Nervosa or Bulimia Nervosa to seek help.

Additionally, professionals are less likely to recognise these males as they may appear healthy and are demonstrating “healthy behaviours.” As such, the following may be indicators of excessive exercise and substance usage related to muscle dysmorphia for males:

- Dehydration

- Cardiovascular complaints

- Heightened anxiety

- Impaired kidney functioning

- Frequent injuries

- Elevated liver enzymes

To date there is no “gold standard” treatment for Muscle Dysmorphia. Recommendations have included the prescription of Antidepressants, Cognitive Behavioural Therapy and Motivational Interviewing. Regardless of treatment modality, it is important that any intervention addresses:

- Psychoeducation regarding risk of body change strategies

- Behavioural strategies to limit body checking, reassurance, avoidance and mirror usage

- Relaxation and mindfulness strategies to better manage/tolerate distress

- Promoting intrinsic self-worth

For more information about anything discussed in this article or to make an appointment with one of our psychologists, please contact CFIH.